- Home

- Nick Courage

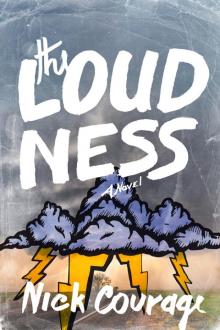

The Loudness Page 13

The Loudness Read online

Page 13

“What’s settled?”

“You’re going to go to the Library and gather the kids inside. I’ll check to see if you’re right about the dam. If the federales are already there, we should evacuate the Zone. And if they’re not, we could maybe . . . do something to stop them. Everyone else can either come with me or help round up people in the Green.” Grammy nods approvingly while Conor and Scott stare at Freckles, agape.

“Okay,” Conor finally says. “If you’re going, I’m going with you.”

“Me too.” Scott shuffles to stand behind Freckles as if we’re choosing teams for kickball. Grammy, smiling tautly, follows him.

“What?” I say. “Everyone’s going but me?”

I want to fight them, but I’m feeling ill again. It’s not my heart, though—it’s a weakness in my knees, an overarching exhaustion weighing me down into acceptance. Limp, my arms flop against my sides, rubbing noisily against the foil. “Who’s going to . . . ?”

I trail off and Grammy finishes my sentence for me: “Round up the troops?”

I nod, exhaling shakily.

“I’ll take care of that, Henry. You just get some—” A sudden hot breeze gusts against the windows, rattling them in their panes. The front door, open since Alice ran away in a panic, bangs against the front of the house. We all shiver despite the heat, thinking about Mouse and my parents, about Alice running home, alone on ominous streets.

We make our way outside with hesitation, checking for black cars. Remembering the aerial photos, I jerk my neck back and scan the skies for helicopters. But there’s nothing, no activity except for the buzz of distant construction and fat and happy bumble bees lazing around Grammy’s hydrangeas. And beneath that, faintly, the steady beating of my artificial heart.

I close my eyes for a moment and focus on the sounds, noises that I’ve heard every day since I can remember. I tell myself to wake up, that this is all just a stupid dream. Dad’s back at home, crushing walnuts for nutraloaf and trying to remember the lyrics to old jazz numbers. Mom’s out fixing the city, but she’ll be home soon too, and we’ll all . . .

A car door opens and I snap to, eyes cracking open with a sudden terror. But it’s just Scott getting into Grammy’s old sedan. I watch as he and Conor and Freckles file solemnly in, letting the severity of the situation slowly sink in again.

This is really happening, I think, forcing myself out of my day-dreams as Grammy pulls me into a tight hug. My aluminum wrap crinkles between us, and I’m suddenly enveloped in her liberally applied perfume. It’s a floral scent I’ve always associated with special occasions.

“I was wrong, Hank,” she whispers sweetly, her lips mashed up against my forehead. “This isn’t growing pains.” I sigh, letting myself be comforted by her closeness, thinking that everything’s going to be all right after all. And then she whispers again, louder, almost savagely:

“This is war.”

She squeezes me one last time and walks with purpose to the car, which she pulls unceremoniously out into the street, not looking back once. Scott and Conor and Freckles, on the other hand, crane their necks until Grammy sharply turns the corner, leaving a rattling hubcap in her wake. They’re not the most inconspicuous group of spies, I realize, shivering at the thought. If the government really has taken control of the dam, she’s driving them all straight into danger.

Feeling acutely alone, I scan the street a second time and start making my way back to School.

The days are long now, and there aren’t many shadows to hide in, but I manage to slink back to School on the shady sides of back streets, checking behind me so often I get a crick in my neck. Every once in a while a truck trundles by and I make myself as small as possible. But I don’t see any more slick strangers. In fact, I don’t see anything other than the occasional contractor.

Despite everything—or maybe because of it—my mind wanders. One moment I’m flattened against a garden wall, terrified; the next, I’m distracted by a handful of green-striped dragonflies, imagining myself in their armored bodies while they flit in and out of the same overflowing garden. To their bulging bug eyes, I’m just splashes of light, segmented and prehistoric.

Like them.

It’s a comforting thought, to be somehow not Henry Long, and—dragonfly-like—I slip into it, my long tail quivering in the heat of the sun. But as soon as I let down my guard, rusty brakes screech in the distance, piercing my foggy insect consciousness. Freezing, I remembering myself and my situation.

That I can’t afford to daydream anymore.

Especially since I keep repeating Grammy’s parting words to myself, mostly in my head, but sometimes out loud like a crazy person. “This is war,” she said. Scott and Conor and Freckles and Gram aren’t going to be storming the dam or anything . . . and it’s not like anyone else in the Zone is a Navy Seal, either. If this is war, it’s not one we have any chance of winning.

A terrible vision stops me cold: Mouse and Grammy and Freckles and the rest of them trussed up in a rust-stained puddle in that burnt-out corner of the warehouse by the dam, Conor straining at restraints that only bite tighter and tighter into his dirty, bloodied wrists.

And then there’s me.

I might as well be with them, considering how much good my body is doing me lately. The more I try to ignore it, the more I obsess about it, hands balled into bony fists; the only constant over the last three days is my spastic heart. And now that the federale government has decided to take over the dam, to drown the city. . . . It was bad enough when it happened naturally, but to do it on purpose? After everything the Zone’s been through; after all the rebuilding?

My fists shake weakly at my sides as I imagine worst-case scenarios: I could die, my parents could die, Grammy could die, everyone could die. The power could spike again and my heart could explode. Everyone could drown. The Other Side could drown. There would be no one left to care.

A dragonfly alights on an azalea bush flowering out over the sidewalk, its tail and wings quivering in the bright afternoon sun.

Except for you, I think. You’ll remember me, right?

A truck rumbles by, trailing construction dust, and I automatically track it with fearful eyes. When I look back, the dragonfly is gone. I’ll have to pick up the pace, especially since I’ve relegated myself to back streets. As I approach the Library from the rear, I hope Grammy’s doing the same—being careful. The Library looks different now—somehow shabbier and smaller. And quiet, more so than usual. Inching around the garden toward the front of the building, on edge, I notice that no one’s milling around in the front yard; there are no dirty-kneed kids squishing bugs. A car door slams and I stop dead in my tracks, breathing loudly despite my best efforts at silence. After a few tortured seconds, my heart pounding dully in my head, I hear what I’ve been praying for: car wheels spinning out on gravel—leaving. With a deep, steeling breath, I peer around the chipped stucco corner of the Library and see a black jeep peeling out down the Avenue, its heavily mirrored windows reflecting the Library in reverse . . . and my own distorted face.

My first instinct is relief, and the tenseness in my chest loosens as I quietly exhale. Crisis averted, I’m just about to step out into the front yard when I see them, out of the corner of my eye: two more black jeeps, parked haphazardly on the streetcar tracks in front of the Library. And leaning against them, three more well-dressed strangers, all in black.

I slump back against the wall.

“Hank!”

The disembodied whisper repeats, and—unable to place it—I scan the garden. A few dragonflies flit around stalks of summer okra, already crowned with delicate yellow flowers. The voice whispers my name again, impatient, and I arch my eyebrows at them disbelievingly.

It couldn’t be . . .

“Henry!” The voice isn’t a whisper anymore, it’s an urgent half-shout, short and sharp like a bark, and I realize with a half-embarrassed start that it’s coming not from the garden at all, but from a window over my shoulder

. Looking up, I see a nondescript girl draped halfway out the windowsill, her face red from hanging upside down.

“Alice!” I shout, wincing almost immediately at her upside-down cringe. Still, I smile to see her. It seems funny to recognize her, unassisted, for the first time when she’s mostly upside down, her sun-bleached hair covering three-quarters of her face. I point to the back of the Library, and she nods, pressing a finger tightly against flushed lips and gesturing toward the Avenue. I quickly retrace my steps, sneaking between the corroded metal book drop and the roughly stuccoed wall to keep out of view and then tip-toeing toward the heavy storm door at the back of the Library. It’s slightly ajar, and so little used that I can’t remember ever having seen it open before. To my surprise, a flash of hands beckon urgently from the darkness within. I look over my shoulder, then make a run for it, only stopping after I’m gripped and pulled into the Library by what feels like a hundred grasping hands.

The darkness inside is sudden and complete.

I have to blink past the fireworks playing against the insides of my eyelids until I see well enough to blame the drapes drawn tightly across the Library’s many windows, which had been thrown open since the Powerdown for circulation and light. Thick and decadent, these have always seemed like one of the last vestiges of Before . . . but now, seeing them through the Zone’s grey veil, I notice that the stately red velvet is balding in spots. The afternoon sun strains against these thinning sections, giving the room a hazy, candlelit feel.

Standing in a semi-circle around me are most of the children from School, with a gaggle of adults standing protectively behind them. Some I recognize and some I don’t. At a desk in the corner, scratching something into a leather-bound ledger by actual candlelight, is Mr. Moonie. Still tugging at my arm, red-faced, is Alice. Standing behind her is Mary, the honey-skinned girl from spin the bottle. Seeing them together again, I’m distracted by a fractured memory of soda buzzing in my veins and Freckles’ thin lips pressed against my cheek. That was just upstairs, less than two days ago. Now, looking at Mary and Alice, ashen-faced in the moldering study, it’s hard to imagine a world where two days ago even existed. “Everyone’s here?” I whisper, not wanting to break the quiet of the room. The last time I’d seen Alice, she was running—wailing—from Grammy’s house. Something must’ve happened between then and now, something that got everyone in the Zone to cram into the darkness. And I have a sinking feeling that it wasn’t Alice spreading the news, door-to-sobbing-door. She nods in affirmation, Mary somberly repeating the nod behind her.

“Almost everyone’s here,” Mary says over Alice’s shoulder. Her voice, loud against the quiet, seems to galvanize the room, which breaks out into hushed whispers. Mr. Moonie finally looks up from his work and seems genuinely surprised to see us, as if he hadn’t noticed us come in. “Half the Green’s here,” she continues. “The jeeps—”

“Half’a the Zone’s here, all right,” Moonie interrupts in a tired voice, rising from his cracked leather chair and shuffling toward us, brandishing his cane at a trio of adults who’d started raising their voices in argument. “First time most of ’em have visited a library.” We laugh out of courtesy, but it’s obvious that beneath his codgerly exterior he’s genuinely upset to have the place overrun.

“Hey, Mr. Moonie,” I say, rubbing my suddenly sweaty hands dry on my shirt, which crinkles uncomfortably beneath my wet palms. He raises an eyebrow at the aluminum foil I’d forgotten about and then gloomily pats me on the back, ignoring my flimsy armor.

“How’s . . .” I try to dredge up some historical personage, a sadsack writer or warrior queen. The generously mustachioed captain of a despite-all-odds flotilla. But everything pales in comparison to this moment; to everyone packed in the library, hiding in the musty darkness.

My parents . . .

“How’s everything?” I manage, lamely.

“World-wracked.” Moonie orates, as if drawing from some dark recess of his memory, and he seems to inflate as he continues, voice deepening. “Gut sacked. Attacked.” He gestures toward the Avenue beyond the drapes with outstretched cane and closes his eyes, looking thirty years younger despite his quivering, chinless neck: “To-night I smell the battle; miles away / Gun-thunder leaps and thuds along the ridge; The spouting shells dig pits in fields of death, / And wounded men, are moaning in the woods.”

The room gets momentarily darker, probably from a passing cloud—but I take it as sign. Grammy had seen it, and now Moonie smells it: war. The closest I’ve come to anything like it is with the Tragedies, and those always came tinged with excitement—swirling green skies and air crackling with static, the preparatory rush and the tight-lipped evacuations. Moonie taps his cane back onto the floor and deflates, an old man in a wrinkled linen suit again.

This feels nothing like the storms.

“Sigfried Sassoon,” Moonie says with a thoughtful sigh, making his way back to his desk, where he flips back through his ledger. An expectant thrill courses through my tensing muscles—an urgency that Moonie doesn’t show any signs of sharing. “No clear ties to the City, none that I knowah. Except, of course, in that . . .” He reaches for a word, looking me searchingly in the eye. His eyebrows are enormous, great white waves cresting up his wrinkled brow. “In that sort of . . . interconnected humanity, shared oversoul . . .” He taps his ledger. “In the Emersonian sense!”

“No clear ties to the city, either, Emerson,” Moonie says, settling back into his chair with a sigh. “But worth knowing anyway. Worth knowing anyway.”

Unable to contain my nervous excitement any longer, I interrupt Mr. Moonie’s historical reveries. “How’d everyone know to come here?” I ask, looking first at Moonie and then back around the room. Only Alice and Mary have stayed in the study—after the excitement of my arrival had dissipated, everyone else moved on to other, less poetic wings of the Library.

“What’s that?” Moonie asks, nose already back in some great and dusty reference book from Before. “I’ve no idea, Mr. Henry Long, why the Zone feels the need to condense into this dead end of a house when any rabbit worth its teeth would be running for the brush.”

Mary, Alice, and I share a nervous glance. “They were driving up and down the Zone, the strangers,” Mary says, the color draining from her face at the memory. “Snatching people.”

“When I realized . . . I started running to my house from your grandmother’s,” Alice cuts in as Mary starts shivering uncontrollably. Her voice is level, but only just. “I had to get my parents. I ran into them on the Avenue. They were racing here, to get me.”

“None of which explains,” Mr. Moonie pipes up from behind his book, the folds of his neck quivering with theatrical indignation, “why all of y’all came to me.”

I catch Alice and Mary’s eyes again. They’re unfocused, with the exhausted looseness of waning adrenalin. No explanation is necessary, and Moonie knows it. Everyone knows it, because everyone feels it: a negative energy. Parents felt it creeping into their consciousnesses and instinctively came to the Library to find their kids. Kids came to the Library because they didn’t know where else to go. Even unattached adults found themselves drawn inextricably here. The Library’s the beating heart of the Green, the de facto town hall. Plus, I think—remembering how fast I went the first time I skateboarded down the sloped driveway—it’s on high ground.

Moonie, its reluctant custodian, knows it. Even cloaked as he is in the past, he smells the coming battle, too. It’s one thing to smell battle, though, and another thing entirely to be a comfortably old historian dropped into the middle of the fray without a musket.

I rub my bare shoulders, suddenly cold. The room has darkened again, and not just because of a passing cloud. It’ll be fully dark in an hour or so, and it’s with a squirming uneasiness that I realize I’m the only person here who knows there’s a possibility that tomorrow we’ll all wake up fifteen feet underwater. My face flushes with shame for having forgotten the only other people who know about t

he plot against the City.

“Grammy’s coming, too,” I say. “And Conor and Scott. They went to the . . .” I pause, feeling Moonie and Alice and Mary’s eyes on me. “She had to check on some things. We’re supposed to meet here at nightfall.”

Moonie checks the dimness of the light slipping in through the threadbare drapes and then considers me for a long moment. “They got some time then, and the nights’re blacker now. Should be easy enough to slip in a little later.”

I nod, turning to leave, and then stop myself. Moonie’s looking at me strangely, his eyes wrinkling up beneath his glasses like he has something he thinks he wants to say, but he’s not quite sure what it is yet.

“Your Gramama . . .”

“Yessir?”

“She got ev’rything she wanted yesterday?”

“Yessir, Mr. Moonie.”

His squint eclipses his eyes completely, and he settles back into his chair with a creak. I wait for a follow-up, but Moonie’s already back in his ledger, more comfortable in Zone history than the actual Zone.

Mary pokes me in the side, loudly crinkling my aluminum corset.

“Okay, Mr. Moonie. I’m gonna go have a look . . .”

“All right, then, Hank,” Moonie interrupts, not looking up. With that, Mary and Alice and I slowly back out of the room and into the Library proper, leaving Mr. Moonie with his books. We’re greeted with the dull roar of what must be the entire Zone condensed into the central hall of the Library, where the old oak circulation desk still stands, corners worn round and slightly worse for wear, beneath a tarnished brass plaque exhorting “SILENCE.”

“What I don’t need,” a red-faced man in an orange vest shouts above the noise, his neck straining with the effort. “Is some slick federale telling me what I can and can’t do!” He wipes the spittle from his bottom lip while his audience, two other men in reflective work vests and a woman I vaguely recognize as one of my mother’s friends, seem to agree.

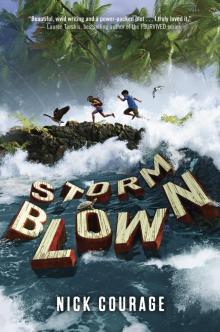

Storm Blown

Storm Blown The Loudness

The Loudness